Leading filmmaker Garin Nugroho is no stranger in France. And one of his masterpieces, Opera Jawa (the Javanese Opera), is transformed into a dance and theater performance for Parisian Quai Branly Museum’s anniversary celebration.

“It was a revelation to discover the vitality of Indonesian creativity in performing arts, within a contemporary context with Nugroho’s film Opera Jawa,” admitted Alain Weber, responsible for performances at Parisian Quai Branly Museum, which features indigenous art, cultures and civilizations from Asia, Africa, Oceania

and the Americas.

The spectacle revolves around the Javanese version on the abduction of Sita episode from the epic Ramayana. The epic has travelled down the ages throughout Asia and fits perfectly into the context of the museum.

Producer Robert van den Bos brought the new version of Opera Jawa, directed by Garin, for 10 days to Theater Claude Levi-Strauss at Quai Branly. It premiered on March 17, and among related events will remain there until March 27 along with a gamelan concert, wayang workshops and three films by Garin, including Opera Jawa.

“Very impressed with the film Opera Jawa, I met Garin Nugroho to discuss future cooperation. I believed he could impart another dimension, like a contemporary twist, to current ideas about Indonesia through novel forms of folk theater,” van den Bos says.

Garin was commissioned to create a new version of Opera Jawa for the Centenary of the Amsterdam Tropenmuseum late 2010.

In Paris, Garin explained the genesis of Opera Jawa for him as a requiem, a work in progress, presented through a combination of gamelan, Javanese song (tembang), dance, costume, acting, visual art and installations.

“It is inspired by Javanese culture that develops and grows in the midst of multicultural expression,” he says.

After his mother’s death, Garin wished to create something based on Central Javanese culture dedicated to her memory. This led to the film Opera Jawa in 2005, commissioned by Austria and produced by Simon Fields to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mozart.

Garin regarded the post-cinematic production as a work in progress because three years later, it morphed into theater production for an European theater festival. Now, it is a dance and theater performance — still called Opera Jawa — here in Paris.

Many admired the film, which features a love triangle involving the three main characters — Siti, wife of the potter Setio and the rich landowner, Ludiro.

But the 90-minute theater production is a more concise, yet original vision of the abduction of Sita, wife of Rama, by Rahwana.

The pivotal difference is that director Garin cannot re-shoot scenes to edit what he wants to be the final cut.

Scenographically at the Tropenmuseum, modern shadow puppets representing elemental forces by Yogya artist Heri Dono were added.

“All are made of recycled cartons with acrylic paint and mounted on bamboo supports. Of course, expressions, costumes and characteristics are thoroughly contemporary,” Heri says.

Purists may find modern accoutre-ments or pop music clash with the finer aspects of Javanese culture. But the discrepancy is what Nugroho portrays as being inevitable in contemporary Java, despite the deeply entrenched traditional world view behind performing and visual arts perduring.

The episode in Paris, named Tusuk Konde because of Sita’s hair-pin decisive role, centers on love, fidelity, passion and vengeance — mixed with elements of wayang wong, a form of Javanese dance theater, together with touches of modern jazz or pop music.

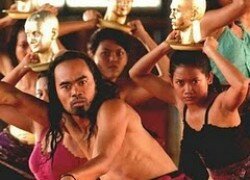

The choir, similar to ancient Greek theater, is represented by dance troupe and singers, who comment the action, while dancing — masked or un-masked, interacting with the three main actors.

In the opening scene, the three actors are covered by huge woven rice holders called kukusan in Indonesian. Uncovered, they reveal the protagonists — Sita, Rama and Rahwana.

Later, in visually striking sequences, these baskets conceal conspirators with bare feet shown slithering on or off-stage, or even hide corpses.

Sita (acted by Dwi Nurul Hidayah) chooses Rama as her life companion, offering him a hair-pin (tusuk konde) in exchange for a lock of his hair sealing their love pact. Later during the absence of Rama, Sita finally cedes to Rahwana despite being protected from temptation by a long red textile held up by female dancers.

Belying his calm personality, when Rama (played by Heru Purwanto) realizes what has happened literally behind his back, he savagely slays his cheeky rival Rahwana, acted by well-known choreographer and dancer Eko Supriyanto.

Finally, contrary to tradition, Sita kills Rama with the beautiful hair-pin which she plucks out of her chignon at a decisive moment — she realizes that her lust for Rahwana was actually the sign of a very strong reciprocal passion.

In Amsterdam late last year, as in the film, it was Rama who killed Sita. However, a group decision during

rehearsals in Paris decided that Sita also had the right to active vengeance.

The opera boldly combines popular, classic and modern forms of music, dance and performance, such as dholak, thayub or kethoprak — drawn from communities in the mountains, beaches and palaces across Central Java.

Dialogues are sung while the action is danced with video excerpts from the film and still photography serving as an occasional backdrop.

Dancers and gamelan players come from the Institute of Arts in Surakarta, Central Java. The troupe in Paris included three actors, 12 dancers and 11 musicians with the extraordinary two female singers — Endah Sri Murwani and Peni Candrarini; lighting expert Iskandar Loedin together with his assistant and Fafa Utami, responsible for costumes incorporating hand-drawn batik.

Garin said that unlike in the past, it was increasingly difficult to find performers capable of both dancing and singing in Javanese style in modern Indonesia.

However, obviously potential sources of great talent still exist in Central Java as witnessed by audience here.

Renowned composer, Rahayuh Supanggah, who composed the music for all versions of Opera Jawa, said that parts of the original film score were used or left out, according to what was felt to be appropriate.

“I was inspired by musical elements from all over Indonesia, not only gamelan, but also by more unconventional instruments.” It’s a job well-done.

— Photos Courtesy of Museum Quai Branly

News Source : The Jakarta Post

Popularity: 2% [?]